We saw him coming from a long way off. We weren’t expecting him, but we saw him coming. He wasn’t very close, this Mr. Taylor, not when we saw him. Not actually. But being where he was, it was close enough. Being where he was, we might as well have been in his ear.

Mr. Taylor had driven through the night long enough to come into morning but morning hadn’t come. Night still painted the quiet country with soot and nowhere in the black distance did purple or orange cut the horizon. Neither did the black hills toward which he drove loom any larger in all the time he’d been fixed on them—they remained distant silhouettes he could smother with his raised thumb. He stooped and pressed his elbows and chest to the wheel and his jaw hung slack and his sleepless eyes moved between the road ahead and the instrument panel. The tank neared empty. In the rearview mirror the long plume of gravel dust behind his car nearly concealed the forest he couldn’t seem to leave behind.

As he descended into another valley, fog sweated from the legions of wilted crop by the roadside, the neck of every stalk broken. Gravel dust powdered it and mixed with the fog. Mr. Taylor tried to breathe but the air was thick as paste and against it his yawn broke into a cough. He rolled up the window. The hills hung framed by his windshield and against them his tires spun, or so it seemed, because he held up his thumb again and there they smothered. He bit a nail and spit it into the passenger seat and found a pill with the chewed fingers in the console and chewed the pill too and swallowed it dry. A mile-marker flashed in the headlights, but its numbers were worn away, just as they all had been. Or else he missed them. He ought to slow down, but the hills were still so far, and car’s tank was nearly empty. He ought to awaken.

“Pay attention. Wake up,” he said aloud.

He pressed himself to the wheel again. The road went straight and flat and white through the distraught fields. There might have been an old barn out in the middle of the fields with a place to hide and rest out of the wind, but only a far and scant reflection of his headlights from what could have been a metal roof gave hint, and in a moment, that treasure was lost in the distance. As he squinted at the field, another mile-marker passed unseen.

His phone had died and with it a map. It laid on the passenger floorboard where he’d thrown it. The clock in the dash displayed 7:30 a.m. but there arose hints of sunrise nowhere. Confusion sobered his face. He would not believe that he had missed a turn. He noticed everything. Like her hair on the bathroom floor and its color and length and thickness. And her clothes in the closet and her underclothes in the dresser. And which were missing. And which smelled unlike her. And he especially noticed the time she left and the time she came home. Everything she touched, every receipt from every trashed grocery bag she ever brought home, every note she penned, every bit of clothing and jewelry she owned went between his fingers, before his eyes, and under his nose and he missed nothing. He would have noticed the turn. What he noticed of this night—that he should have been somewhere, anywhere by now—was all that could be noticed. He had made no wrong turn; there had been no turns at all.

He squeezed the steering wheel like he meant to choke it to death till the muscles in his hands cramped. He slapped his cheeks and rubbed his eyes. When he opened his eyes again, he threw himself back into the seat and floored the brake pedal. A faded stop sign ran across the headlights and the car stuttered then jolted to a stop, throwing his head into the steering wheel and the horn into the shattered quiet. The headlights illuminated an old pickup truck backed just inside the trees beside the gateway to a narrow bridge, the extent of which lay hidden in the fog. He parked the car.

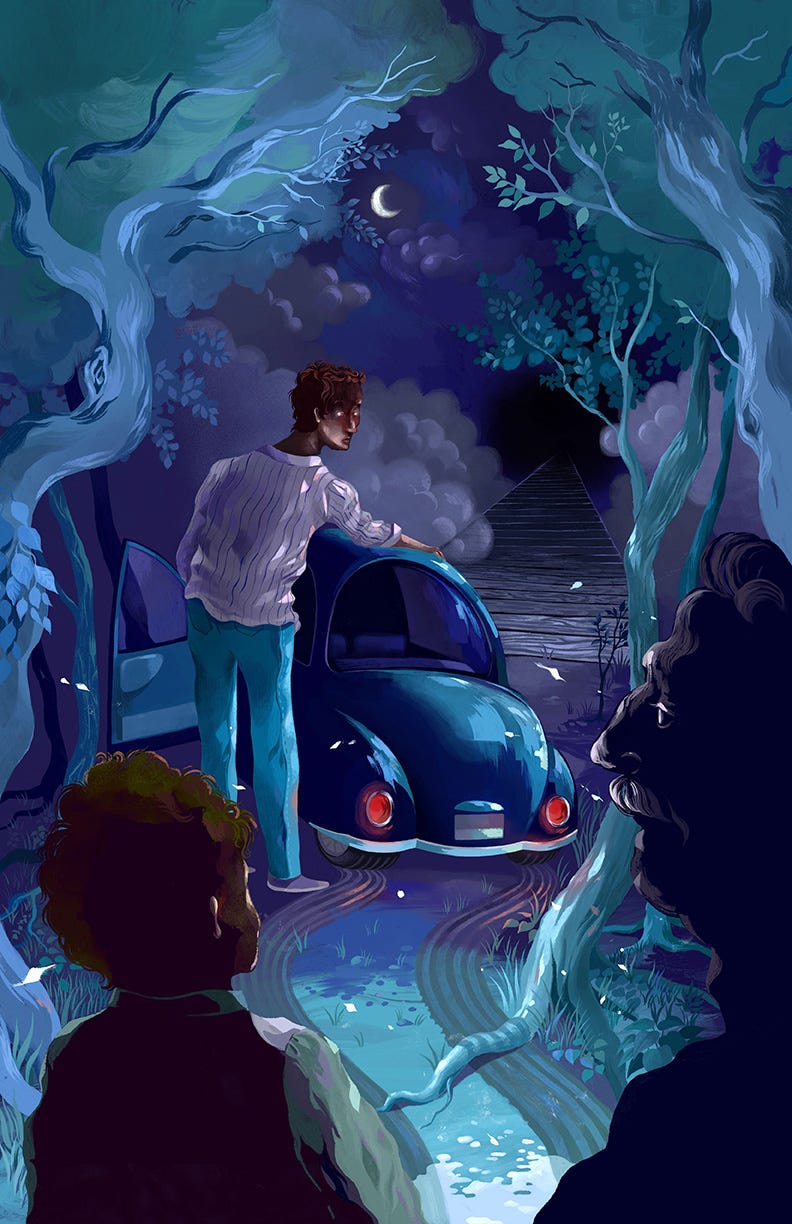

“Get ahold on yourself,” he said aloud between heaving breaths, then slapped himself on both cheeks again. He cracked his door and at the same time both doors on the pickup truck under the trees opened and two men stepped out. Mr. Taylor spun toward his back seat. The armrest dividing the center of the bench seat had fallen open and spilled out the bloodstained Oxford shirt that had been hidden there with the rest of the clothes. Two long golden hairs stuck coiled in the stain. Her hairs on his shirt. He couldn’t reach it. Mr. Taylor got out and met the men—one old, one young—a few paces from the front of the car. The young man stood outside the brightest glow of the headlights, but his face was boyish and limp with sickness and spoiled by ugly pocks. The old man, fully alight, appeared as ancient as the young man did sick.

“Evening,” Mr. Taylor said.

“Who’re you?” said the old man.

“I'm lost, I'd say,” Mr. Taylor said. He faked a smile.

“Your name. I want your name.”

“You call me Mr. Taylor.”

“Where’re you coming from, Mr. Taylor?” the old man said.

“Kansas. I come all the way down from Kansas.”

“Kansas. Whereabouts?"

"Topeka. Leavenworth. Here and there. There and here if you get my meaning," Mr. Taylor said.

"How far south you going?” said the young man, speaking in a whisper that barely escaped the hum of the car engine.

“Depends. You two live out here?”

“No one lives out here,” the young man said, and the old man nodded.

“I’m aiming for some place I can sleep and get fuel,” Mr. Taylor said. "You don't got a gas can in the back of that truck, do you?"

"Not gas, no," the old man said. The young man grinned a closed-mouth grin.

Mr. Taylor spat. "I would guess not. Point me on, then," he said.

“You have to go a long way,” the old man said.

“I’ve come a long way. I take it there is a town on the other side of this bridge. I thought I’d see lights up one of these hills, but I don’t see jack through the fog and the hills are farther than they look. I’m low on gas. If you live near, I got eight dollars for a meal.”

“No town over there,” the young man said. “If there was a town over there you wouldn’t be able to see the stars.”

“I don’t care much for stars,” said Mr. Taylor.

“You can’t cross anyway. Can’t have two cars on the bridge at once,” the young man said.

“I don’t see no one else,” said Mr. Taylor, looking at the bridge. The trusswork creaked in the wind.

“You didn’t see the stop sign neither," said the young man. He wiped his nose with his arm from elbow to fingertip then flicked his hand and added, "You didn't, did you?”

“He didn’t see us neither,” said the old man.

“I saw it well enough. Just not soon enough,” Mr. Taylor said impatiently. He looked back at his car. “I’m stopped, ain’t I? Come on, boys. My car’s still running. And I hit my head on the wheel when I hit the brakes.”

“I’m not sure what you want, Mr. Taylor,” the old man said, dragging his foot back and forth on the gravel.

“Lend me one of your phones,” Mr. Taylor said.

“What?” the old man said, holding his hand to his ear.

“My phone is dead. I need to borrow yours.”

“What for?”

“I'd like to see a map, maybe call a tow if there isn’t fuel nearby. Didn’t I tell you that I'm lost and I need fuel? The car is running on fumes. Can you point me where to go after this bridge or am I going to have to break into your truck and find a way to help myself?” said Mr. Taylor with the tone of a joke and a straight face.

“We ain't got no phones,” said the old man, squinting into the headlights. “But I know what’s beyond the bridge"—he nodded in the bridge’s direction—“and it ain’t sleep. You done passed by all that, or else it passed you and you didn’t recognize it. Even if you could find sleep over there, you’d have to get over the bridge first and that just isn’t going to be possible. That bridge is old as I am. It’s just bones left. If you don’t cross it lightly, you’ll get it swaying and dump yourself off the side. You don’t want to get dumped off, put a coin on that.”

“You don’t want to get dumped off the bridge,” added the young man.

“It’s a long bridge. Goes all the way over. All the way, see? I recommend you turn on around and go back,” the old man said.

“Piss on that,” said Mr. Taylor.

“Piss on it then,” said the old man. “You still won’t get across it, put a coin on that. It sags in the middle. You can’t tell it from here but it sags and catches a cadence on windy nights like this and it’ll send you off the side if you don’t turn back. The bridge is so long there’s a good chance, really there’s a perfect chance that before you get to the other side, another vehicle will come up from the other side and at that point you’ve got to back up to this side again anyway. Like my friend said, we certainly can’t have two of you on the bridge at once.”

“I’ll be all right,” said Mr. Taylor. He laughed. “I’ll be just fine. If you knew who I was, you’d know a high bridge don’t mean jack to me. You’d know it wouldn’t be me backing up. Not if push come to shove.”

“Push come to shove wouldn’t end well for anyone. Not for you leastways,” said the young man, and Mr. Taylor, with the sweat that had beaded on his forehead beginning to drip down his cheeks, started to answer him, but the old man interrupted and continued as if he had heard neither of them.

“Even if you make it across the bridge and back on the road, the road doesn’t end and the forest has a radius unfathomable, see. My own self can’t fathom it. The trees, look at them! You can’t count them, and if you can’t count them, you can’t drive past them. If you make it past one hundred trees, you’ve still got two hundred trees to pass. And if you make it past two hundred trees, you’ve got five-hundred trees yet still to go. And then a thousand. And a thousand-thousand. And if by grace you make it out of the forest, which just gets thicker the farther you go, even then you would still be only at the beginning of it, since we sit at its beginning right here. If you were to get out of it, you’d be at the end. But you’re at the beginning now, you see? Beginnings aren’t connected with ends, not physically, elsewise they wouldn’t be neither a beginning or end, they’d be one and the same. How can you go between two things not physically connected?”—the old man knelt and picked up a chunk of gravel and with a little effort chucked it off the side of the bluff and brushed his hands together—“You can’t. You’ll never make it through. Not even across the bridge. Did I tell you about the bridge? If by decadence of grace you traveled across the bridge”—the old man trailed off—“If by decadence of grace—” he muttered, then, “But the trees! You’d never find your way into open country except maybe into a valley that would just take you up another bluff like this one, where you’d see if the fog lifted more trees around you than stars over our heads. You’d be back quick in so many trees you’d think you’d never come out of these ones here in the first place. And wouldn’t that be the truth? They’re all the same. One is the next and the next is the other. That’s how the whole way goes, Mr. Taylor. It doesn’t end. None of it. And even if it did, you can’t cross. It just isn’t possible. You can travel but you can’t go anywhere. By God, not from here.”

“By God, why on Earth would you come down this way?” the young man added.

“What in the hell is wrong with you, old man? You palsied like the boy? Tell me where I can catch some rest and fuel up. You’re done wasting my time,” Mr. Taylor said, then, feeling instinctively for his knife, which he hadn't on him, added, "I've half a mind to take what’s yours whether you like it or not."

The old man stood straighter and looked at the young man, who after a moment stepped from the shadow into the headlight beams. He smiled. His skin, the color of the belly of a fish, lifted at the corners of the mouth and showed his bloodied teeth and swollen gums. He wiped his nose and said, “I ain’t a boy.”

Mr. Taylor recoiled at the young man’s features, which, now that he could see them clearly, were shaped boyishly but twisted with disfigurement. Silence engulfed them but for the bickering of the insects until Mr. Taylor said, “I got somewhere to be. You boys have the night you deserve."

“Won’t we,” said the old man, and his smile cut a hole in Mr. Taylor's skin and crawled underneath. Mr. Taylor went quickly back to his car and by the time he had closed the door and beat the steering wheel with his palms, the two men had disappeared into their truck. Through the overhanging branches scratching at the dark windshield of the men’s truck, the bloodied teeth of the young man smiled at him. He restrained himself and put the car in drive and went slowly toward the bridge, paused before its decking, then charged onto it.

When the low-fuel light came on he had long ago parked, chilled stiff by the wind that slipped through the jambs. Thus paralyzed, his gaze had been fixed on the darkness besetting the bridge and the fog still wafting up from below. The passenger seat was now littered with fingernails and the bridge wavered loosely under the weight of the car and against the wind. The bridge’s oscillations had stuck him—as they grew larger, he went slower until he stopped, and every time he’d tried to start forward again, a great mechanical moan screamed before the tires went even one time around. Shortly, with even an infinitesimal turn of the tires, the bridge started at him again. No end of it was in sight, neither before him nor the way he’d come. The decrepit steel, the missing crossbeams, the deep corrosion, the missing decking—of the bridge, these he saw in the dark, but no end.

The decision he could not make—that is, what to do next—was shortly made for him when through the windshield at some indeterminable distance two soft-glowing orbs appeared and grew larger before his eyes until they took the familiar shape of headlights. In a moment, Mr. Taylor began reversing slowly but immediately felt the speedbump at the bridge’s gateway. The old pickup truck sat still dead in the trees and the sickly young man leaned with his elbow against the hood with his head in his hand dreamily watching Mr. Taylor. The old man sat in the driver’s seat with the door open dangling his feet like a child. Mr. Taylor threw himself from the car and approached them with a comfortable and quick aggression but was arrested by the force of the old man's voice as he neared.

"Stop there, boy,” the old man said, coming nimbly out from the truck.

Mr. Taylor stopped on his heels but said, "Call me a boy again and I'll break you like a slut, old man. Say it again."

"Settle down," said the old man, "Didn't I tell you that you would have hell getting across the bridge? The boards making up that deck are infinite, didn't I say? Or didn’t I. I should have told you the boards in that decking are infinite. Do you know what that means? It means to count all the boards in that decking you can never stop counting. And you know, any one of them boards can be divided up an infinite number of times. Basic arithmetic tells you that, don't it Mr. Taylor? Or didn't you learn basic arithmetic in Kansas? Or aren’t you just a stupid boy too slow for arithmetic?”

Mr. Taylor started forward, but the old man’s voice arrested him again: “You can take one board and divide it by two and two again till you die for counting, and even if you lived forever you could keep dividing until you’d forgotten why you started. Nothing ever goes away when you divide, Mr. Taylor. The pieces only get smaller and smaller. Do you know what that means? It means that to cross even one of them boards you got to cross half of it first, but before you can cross half of it, you got to cross a quarter of it, all the way to infinity. To infinity, Mr. Taylor! Do you see? I never heard of any man crossing an infinite number of distances, did you? Not by automobile, not by foot, not by anyhow. It’s unfathomable, I should have said. You didn't truly expect to cross that bridge, did you? After what I already told you? Never mind the trees. The bridge! It’s impassable. You should have known by what I’d said. Tell an old man the truth of it. Are you just as stupid as you come off?"

Mr. Taylor's hands were numb. The chill from the wind slowed his blood. He could still feel his feet well enough, and yet he couldn't move those either. No, it was the words of the old man and the ugly smile of that young one next to him that stopped him like buckshot to the chest.

“I’m telling you now to end the show. Then I’m showing you who I am," said Mr. Taylor.

"You're a killer. From Kansas, I take.”

"You’re a quick study, then," said Mr. Taylor.

“I seen the shirt in the car. And the hair, pretty hair it is,” said the old man.

Mr. Taylor rubbed his dripping forehead, nodded at the young man and said, "Can you run as well as the old man sees?"

The old man and his younger companion bent wildly and laughed the laugh of coyotes and the young man barely managed his convulsions enough to point behind Mr. Taylor and say in turn, “Can you?”

Two figures emerged from the fog, these not old and not sickly men but a breed of unyielding mass equal to the darkness that would not lift this night and whose heaving energy became furious the closer they came. Mr. Taylor watched them with open, empty eyes until the last moment when he ran to the car. He pressed the gas pedal to the floor and the car rolled and the engine died and the car came to rest. In an instant he was pulled wild and thrashing from the car to the pavement and bound, gagged, stilled, and dragged over the pavement to the grass beside the bridge. The approaching headlights were as bright as two suns trapped within the arches, but as the two figures forced Mr. Taylor’s head over the edge of the knoll, their light extinguished and all he saw were the bridge abutments disappearing into the blackness below. The figures flipped him flailing on his back, whereby he witnessed the captors and became stiller yet and voiceless.

One captor leaned just above his face so the oily breath fell from the gaping mouth onto Mr. Taylor's nose and dripped down the cheek. The eyes above the gaping mouth judged Mr. Taylor hopelessly. The mouth moved and words spilled out and together the captors threw him from the bluff into the vast black air below.

Mr. Taylor fell, and while falling he woke. Supine on a gurney with his arms locked at his sides, he shivered desperately. So many downcast eyes from long faces pressed into him. One face came very close, obscured behind the blurry beam of a penlight—now two lights floating before his half-conscious daze. Mr. Taylor tried to sit up. From behind the penlight came the words:

“More. Mr. Taylor is not unconscious.”

“It’s 7:34. We’re four minutes past,” said another voice in a breath of panic.

“He’s trying to rise,” came yet another voice.

From behind a glass window, a crowd gasped. In the execution room, a doctor loaded potassium chloride into another syringe and plunged it into a vein.

Mr. Taylor was falling again. The blackness opened to receive him like the pincers of the stag beetle. The words whispered to him before he’d been cast down whistled like the wind about the valley and through his head, fomenting his terror: “You've made yourself known, boy. Now get to know us.”

And we laughed, didn’t we? Coyotes laughed hidden among the fog.

This starts off awesome-totally into it from the get-go...(BREAK to take care of stuff)...and continues in much the same vein. From the beginning to end thoroughly enjoyed your rich language, which reached a dazzling peak with "the pincers of the stag beetle." The language reminds me once again that prose, and, like, words, don't ever need to be as boring and as "nichtssagend" (the awesome German word for it-literally "say nothing") as the language we all hear every day on the news, in the papers, and on (ugh) social media. You can be very proud, and I wish the world would be more appreciative of such efforts. It has value, where plagiarized Harry Potter garbage and the like does not. Thanks for this.